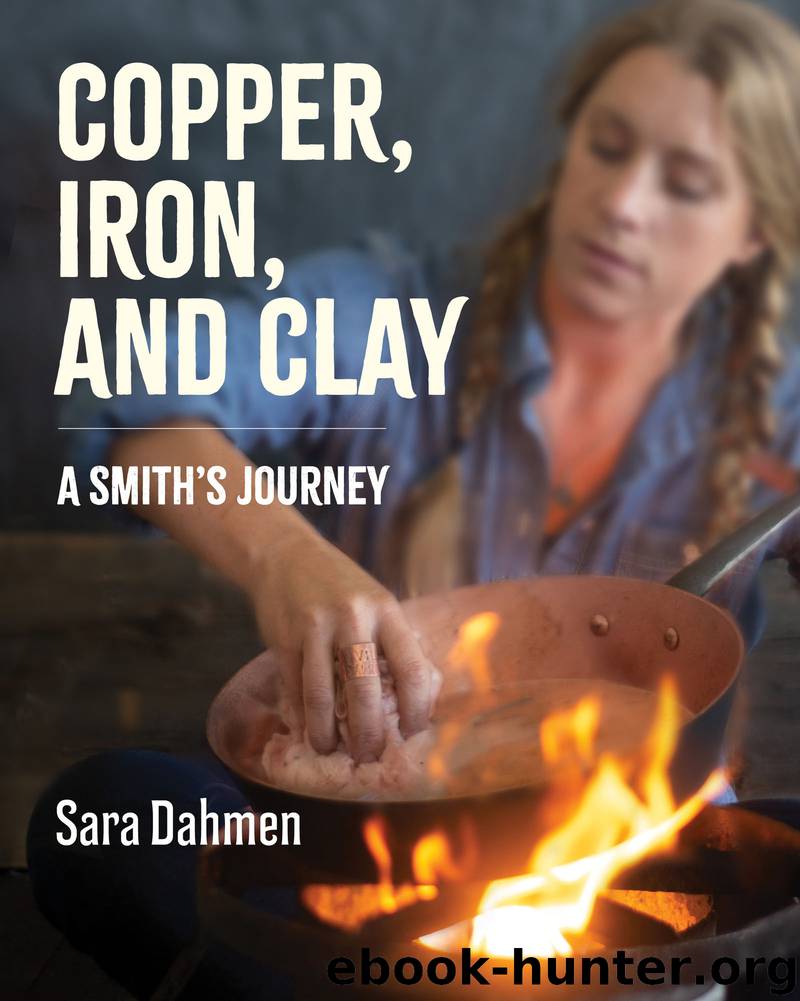

Copper, Iron, and Clay by Sara Dahmen

Author:Sara Dahmen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

Published: 2020-04-02T00:00:00+00:00

* * *

FORGING AHEAD: TODAY’S CAST IRON

As technology advanced, with the invention of steam power and then, a bit later, the Industrial Revolution, a large chunk of the manual labor previously required throughout the casting process was eliminated, and high-quality iron became readily available at a lower price. This led to the creation of cooking pots and pans that look similar to our modern ones.

One of the major advances in cast-iron creation was the widespread use of the blast furnace. These furnaces are vertical structures in which suitable heat is maintained to allow intense combustion (the perfect fire!) by blasting air into alternating layers of charcoal (and, later, coke), flux (crushed seashells or limestone), and iron ore. A blast furnace can process (make purer) many different metals from copper to lead to iron, but its initial invention was mainly for the purpose of creating different irons, the most common being pig iron, a rough ingredient for creating cast iron. The iron running off a blast furnace can be poured into molds depending on what you’re making—pig iron mix is poured into ingot shapes for easier transport and later melting, whereas purer cast iron is put into more familiar cookware molds, for instance.

The blast furnace was developed from smaller furnaces dating back to Roman times and grew in size over the centuries. They appeared during the Middle Ages in western Europe, but archaeological evidence points to these furnaces being invented separately in China and Africa, too, at a slightly earlier time, though the dates are uncertain. France and Belgium operated the furnaces as early as the mid-twelfth century, and the casting of iron pots quickly became lucrative if you had enough funds to build a furnace and pay workers. Additionally, once the smiths understood how to make curved and hollowed pieces for—you guessed it—warfare items like cannons, these skills also allowed for numerous new styles of pots for kitchens.

Then, in 1707, Englishman Andrew Darby revealed his sand-casting innovation, which allowed for a design to be made in sand forms so that a single design could be made over and over very efficiently. Sand-casting had been tinkered with as early as the 1540s, but Darby’s methods could be replicated without too many explosively unexpected results. No more “breaking the mold,” as was needed with wax casting. Darby’s patented process revolutionized cast iron, which became inexpensive, quick to produce, and available to all income levels. Iron began to be cast from pig iron and leftover scrap iron (basically the castoffs from castings that didn’t look nice or broke) in larger and larger quantities. The cooking landscape changed again.

Shortly after Darby’s patent took off, blast furnaces were largely replaced by cupola furnaces, which used the same combination of charcoal (and coke in later years), limestone, air, and iron ore, but the big difference was that they could be heated constantly, melting iron at a much more rapid pace and allowing for even greater production of cast-iron goods. Blast furnaces continued to create the more

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4226)

The Doodle Revolution by Sunni Brown(4055)

A Simplified Life by Emily Ley(3584)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3176)

Marijuana Grower's Handbook by Ed Rosenthal(3131)

Paper Parties by Erin Hung(3048)

Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook by Better Homes & Gardens(2966)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(2807)

Draw Your Day by Samantha Dion Baker(2717)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2619)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(2564)

Lions and Lace by Meagan Mckinney(2499)

Dangerous Girls by Haas Abigail(2483)

The Curated Closet by Anuschka Rees(2398)

Zero to Make by David Lang(2352)

How to Make Your Own Soap by Sally Hornsey(2348)

The Wardrobe Wakeup by Lois Joy Johnson(2240)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(2222)

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande(2209)